Someone once told me that the direction that written languages follow – left to right, right to left, top to bottom – was due to the tools that influenced their development. I remember the anecdote more than the teller, but, basically, Hebrew is right to left because right-handed people hold the chisel in their left hand and hammer in their right. By contrast, East Asian scripts evolved from the way a brush is held between the fingers in the right hand, and European scripts relied on tools that encouraged right to left. It’s a simple technological determinist reason – but is it true? Some languages may well have been influenced in this way, but does that mean this is how all language develops? It certainly highlights a sense of relationship to history and the world: that there is a rule, singular, for why x is like y. If, say, Hebrew was developed with the pen, perhaps it would flow north-west to east instead.

Someone once told me that the direction that written languages follow – left to right, right to left, top to bottom – was due to the tools that influenced their development. I remember the anecdote more than the teller, but, basically, Hebrew is right to left because right-handed people hold the chisel in their left hand and hammer in their right. By contrast, East Asian scripts evolved from the way a brush is held between the fingers in the right hand, and European scripts relied on tools that encouraged right to left. It’s a simple technological determinist reason – but is it true? Some languages may well have been influenced in this way, but does that mean this is how all language develops? It certainly highlights a sense of relationship to history and the world: that there is a rule, singular, for why x is like y. If, say, Hebrew was developed with the pen, perhaps it would flow north-west to east instead.

In other words, I suspect it isn’t just technology that determines our languages.

Most of our writing traditions are still situated within print traditions and we employ a lot of metaphors to support this – webpages and ebooks, for example. But in reality, the structure and content of these traditions are actually publishing traditions. That is, the economy and process of producing and selling a book has suggested the physical structure of a book: the standardisation of print, the creation of an author, the separation from the material presence – the writing itself – and the ideas within the book.

In publishing, the material presence is not part of the authorial process; instead, it belongs to the production of the book. The manuscript moves from editorial, to design for layout, and marketing for cover and positioning. Now, somewhere along the line, it will be converted into an ebook, the text reflowing like the idealised narrative freed from its material chains.

The difference between the economic and technical constraints has, I think, an analogy in the supermarket self-checkout. When supermarkets started installing self-checkout it was in the name of efficiency: people would more easily be able to buy their own food (and, purely coincidentally, the supermarkets would be able to hire less staff). That was the theory. But how in practice has it actually turned out? Is the Coles self-checkout the most efficient way to organise or distribute food? Of course not! On an efficiency scale, it would be much better to let people help themselves to whatever they want. Which, in a roundabout way, brings me back to books: our print traditions are not so much influenced by the restrictions of producing a book as by the economics of producing a book.

Our print traditions include the famous likes of William Blake and Stéphane Mallarmé. Blake’s writing and etchings blend together, forming a unique kind of work, one that cannot quite be described as decorative text, nor as illustrated writing. (As can be seen in this attractive online copy of Songs of Innocence and of Experience).

Mallarmé’s Un coup de dés, on the other hand, uses space and text to produce multiple readings. It is worth noting that both these works are poetry. The material form is always significant to poetry; exploration and experimentation of the material form underpins poetic writing. Poetry manifests this in written, spoken, and electronic forms through the use of whitespace, linebreaks, shifted text, rhythm, rhyme, disruption, tone, alliteration, movement and numerous other techniques.

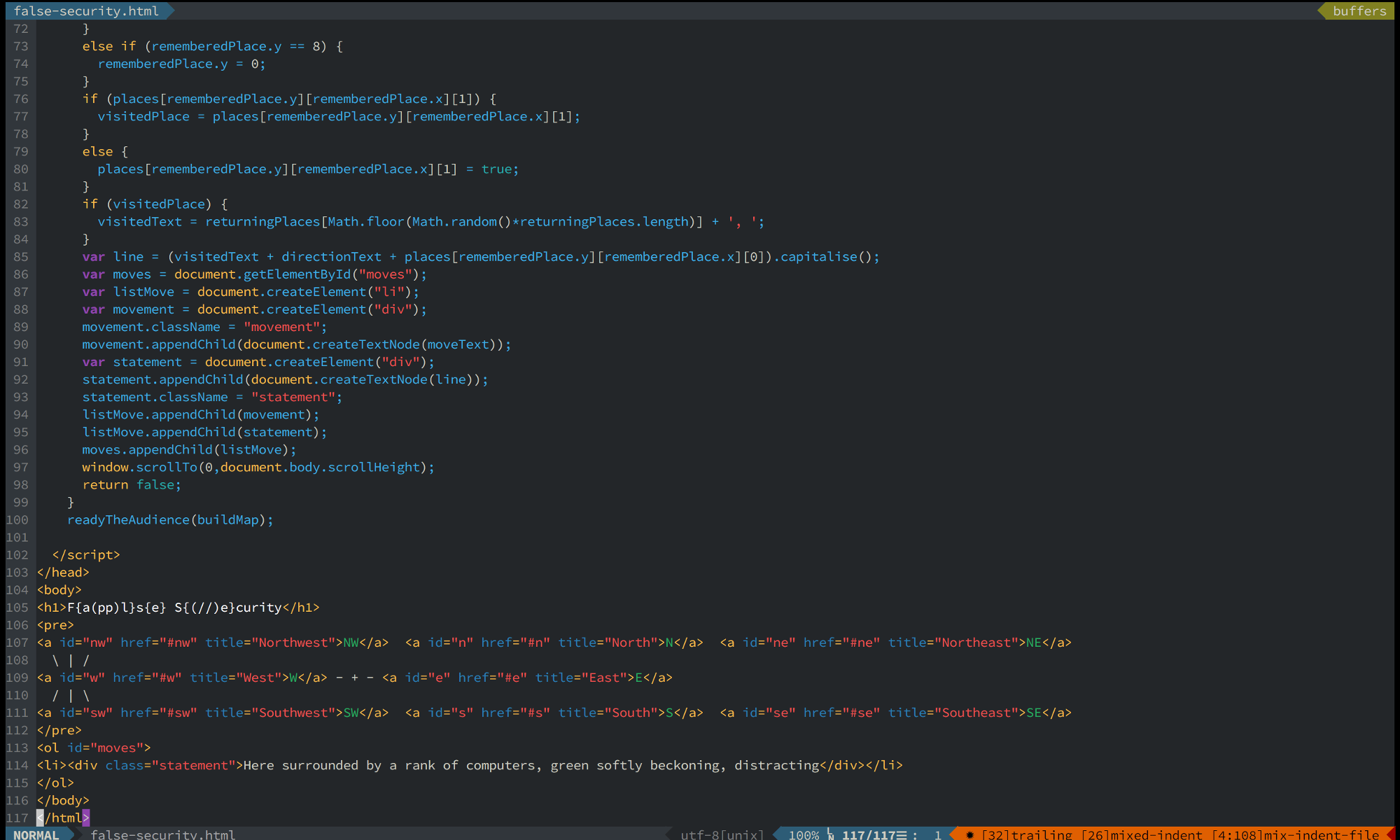

Recently for the Overland website I marked up Patrick Jones’s ‘Step by step’. Unlike a poem in print, where the layout transitions from the electronic file (InDesign) to the print representation (the journal), on the web this layout is persistent – that is, the mark-up language is the only thing holding that poem together. The (X)HTML and CSS language that formats and displays the poem isn’t merely presentation.

Underlying publishing on the web is the notion of separation of form or appearance (CSS) from content (HTML). Added to this is the expectation that webpages are semantic or literally meaningful. Content is comprised of both the textual content and the (X)HTML semantic content (such as a paragraph tag to indicate the textual content is a paragraph or a heading tag to indicate that the content is a heading). But when you take (X)HTML and add the Semantic web, the meaning is extended to metadata that further describes content. So by adding metadata to the (X)HTML – RDFa (Resource Description Framework in attributes) for instance – programmers can identify an article tag in HTML5 as a blog post or review and can identify a paragraph tag under a heading as an author of a post.

What does this mean for poetry?

Both the semantic and Semantic web are intended for the machines. It is the search engines, databases, scrapers and other tools that pull this data together. It allows search engines to prioritise and display the information specific to the kind of content it is (like including stars on reviews in a Google search). When HTML5 was being developed, some programmers advocated for special poetry elements to be added to the specification. While elements such as ‘article’ were included, no elements particular to poetry were.

If materiality is significant to poetry, how can we make dynamically meaningful poetics like ‘Step by step’ in the linearly structured, static medium? After all, poetry is a form that explicitly entangles meaning.

These questions aren’t solely for the web either. The structure of an ebook is built on web technologies. It is a structure that displays the familiar print layout in a format where form follows device design. It’s a structure that eschews physicality and the materiality of print. The ebook format has largely neglected poetry. The economics of production trump the transition of print-poetry forms to ebook format, and it’s hardly a surprise. A brief look at the companies involved in the production of the standard shows that it is unlikely poetry will ever be a priority.

I’m not saying that there aren’t poetry ebooks, because of course there are. But I am saying that the materiality of print poetry wasn’t embraced in those ebooks. As it stands, a move to the ebook form requires compromises from poets, and perhaps it would be better to write this poetry with an awareness of the material factors of ebooks. Precisely because of the importance of materiality to poetry, the poetry ebook shouldn’t just be seen as an equivalent format with a different distribution model. The production of literature isn’t that neutral for a start.

This post was originally published on the Overland literary journal website as part of the Meanland project: If William Blake were going to make a poetry ebook.