This is how I feel every time I say the word ‘digital’. Given I’ve been saying it for a long time now, it’s starting to become a problem.

Last year, on the wall in Little Lonsdale Street where I have a post office box, Australia Post added parcel collection boxes. It used to be the only time you could pick up mail was in the morning before 9.30am. Now, instead of getting a parcel pick-up notice, you receive an electronic key attached to a big red rectangular piece of plastic with the box number on it. Yesterday I got a key for such a box. But when I pressed the round key against the lock it groaned electronically and flashed red. I tried twice more before giving up and going to the post office. The Australia Post staff member who helped me offered that the battery may have been flat and that, actually, they were only trialling the boxes anyway.

What this technology was preventing me from collecting (the things that were actually inside the box) were two literary journals I subscribe to: the latest issues of Southerly and Island. If technology was going to thwart anything, I’d expect it to be a literary journal. Fittingly enough the current issue of Island is ‘Digitalism’, dedicated to the ‘digital’. It has a collection of essays tackling self-publishing, literary participation and the Australian book publishing industry. Southerly has, as always, two tables of contents: one for print articles and one for their online articles, ‘The long paddock’. The poems, stories, essays, reviews and interviews in ‘The long paddock’ weren’t actually printed in that issue of Southerly – so does that make them digital in nature?

What this technology was preventing me from collecting (the things that were actually inside the box) were two literary journals I subscribe to: the latest issues of Southerly and Island. If technology was going to thwart anything, I’d expect it to be a literary journal. Fittingly enough the current issue of Island is ‘Digitalism’, dedicated to the ‘digital’. It has a collection of essays tackling self-publishing, literary participation and the Australian book publishing industry. Southerly has, as always, two tables of contents: one for print articles and one for their online articles, ‘The long paddock’. The poems, stories, essays, reviews and interviews in ‘The long paddock’ weren’t actually printed in that issue of Southerly – so does that make them digital in nature?

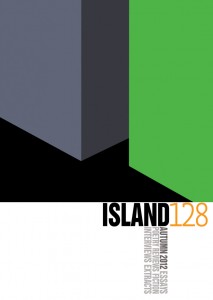

In a review of the Electronic literature collection V2, Tim Wright questioned the term ‘electronic’ on a similar basis: ‘Understood broadly it could include any piece of literature making use of an electronic technology – e.g. Microsoft Word – somewhere along the line. What literature today isn’t electronic? might be the more productive question to start with.’

The problem as I see it with ‘digital’, and to some extent ‘electronic’ (as in ebook), is that they are applied so generally that they are rendered almost useless. For all intents and purposes, particularly in this period of greater non-print publishing, many texts are not printed.

At least the titles and authors of the poems in Southerly’s ‘The long paddock’ appear in the journal’s contents page. If we examine the life-cycle of a poem in a journal such as Cordite, where Wright’s review was published, the poem might never even approach a piece of paper. The poem can be constructed with word-processing software, uploaded or attached to an email and then entered into the online system, such as WordPress. Proofing and publication may also be conducted online.

These ideas about ‘digital’ also appeared in a post by Emily Stewart, on Cordite’s Guncotton blog, regarding the digital publishing of poetry.

When we take a sideways step and look at digital poetry outside of its book ‘container’, we see not only that it is flourishing, but that it has been growing and evolving for long enough to have formed established genealogies of networks and readerships. Cordite’s been going strong online for over ten years.

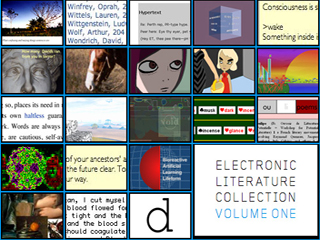

Is publishing online all that is needed to make something digital? Or if not just that, does adding hyperlinks make an online piece digital?

Is publishing online all that is needed to make something digital? Or if not just that, does adding hyperlinks make an online piece digital?

Print books have had some degree of unidirectional linking, through footnotes and bibliographies, for quite some time. But these linkings occasionally fail when translated into an ebook. For instance, Jay David Bolter’s Writing space: computers, hypertext and the remediation of print contains internal text linking, as indicated by markers: ‘the marker (= > p. 23) following a sentence indicates that the reader can find a related discussion on page 23’. Yet, the ebook version I own doesn’t take advantage of the medium to make those actual links.

It follows that perhaps we need more than hyperlinks to define something as digital. So what about comments? Can a text be described as digital if comments are enabled?

In actual fact, we can work with computers and the online space in many different ways. We can use them to publish poetry, essays, and short stories that would otherwise appear in print, and as a method of distribution – a practice that started with DIY publishing. We can also use them to communicate, publicise and market what we publish. Rather than merely replicating what we do in the print space online, we need to find out what makes the online, computational and networked space unique. How truly ‘electronic’ or ‘digital’ can a text be if we only employed the computer to optimise production and delivery? Roberto Simanowski argues, in his essay ‘What is and toward what end do we read digital literature?’, that by its very definition ‘digital literature must be more than just literature otherwise it is only literature in digital media’.

So what should be called digital literature? Digital literature as defined by Simanowski applies to most of the works in the Electronic literature collection V1 and V2, which are all worth reading. These works hinge on the computational aspects of their media to produce meaning and to express a literary experience.

Unfortunately, markets and companies have a lot of control over the direction a word takes, like labelling the non-print versions of books digital. Alternative adjectives include ‘enhanced’. In ‘Book sales have fallen off a cliff: What next for the Australian publishing industry’, in the Digitalism issue of Island, Tim Coronel notes ‘ebooks don’t have to just replicate the structure and forms of their print counterparts: “enhanced” ebooks can incorporate multimedia elements; collaborate and multimedia elements are possible, with multiple authors and/or reader participation in steering the direction/s of the story’.

Is it helpful to call both ‘enhanced’ ebooks and reformatted print books ebooks? Ebook doesn’t indicate anything about the content or form, nor much about their delivery or technical compatibilities (Amazon or EPUB, DRM or non-DRM for instance).

The term ‘digital born’ is now becoming an alternative to digital. It suggests both a work created on a computer, and for display and interaction on a computer – and precludes printing. But this means it excludes programmable works that are generated with computers but are easily printed, such as the poetry on Gnoetry daily.

I don’t know how the usage of ‘digital’ will evolve, but I think what we need is more specificity. The question is what would that specificity be? Perhaps I’ll adopt the terminology of practitioner and theorist John Cayley, who explains that he writes in networked and programmable media. And from now on I’ll be trying to avoid the word digital.

This post was originally published on the Overland literary journal website as part of the Meanland project: Digital – you keep using that word!